How Many Ventilators Do We Need?

For many of us that have not visited an (ICU) intensive care unit recently, we probably haven’t thought too much about ventilators. That was all to change in 2020 with the Covid-19 pandemic. Suddenly the world was thrown into a frenzied panic over shortages of essential goods and services – from toilet paper to hand sanitizers to masks to beds and to ventilators.

For many of us that have not visited an (ICU) intensive care unit recently, we probably haven’t thought too much about ventilators. That was all to change in 2020 with the Covid-19 pandemic. Suddenly the world was thrown into a frenzied panic over shortages of essential goods and services – from toilet paper to hand sanitizers to masks to beds and to ventilators.

Mainstream media provided viewers with daily sensationalist reports of hospitals being overwhelmed and a critical shortage of ventilators and other PPE (personal protective equipment). We discovered the national stockpile of such equipment had not been replenished by previous Administrations and were now empty.

Citing unmitigated ICU needs being overwhelmed by Covid-19, public health advocates and officials then introduced us to some concepts like flatten the curve and social distancing, to reduce the need of available ICU beds and ventilator capacity. While about 80% of people who contract the virus have relatively mild disease, the rest may need hospital care. Up to a quarter of those may need intensive care, which often includes time on a ventilator.

Citing unmitigated ICU needs being overwhelmed by Covid-19, public health advocates and officials then introduced us to some concepts like flatten the curve and social distancing, to reduce the need of available ICU beds and ventilator capacity. While about 80% of people who contract the virus have relatively mild disease, the rest may need hospital care. Up to a quarter of those may need intensive care, which often includes time on a ventilator.

When it was determined the official infection numbers were vastly overestimated and the existing hospital capacity was adequate, these same public health officials claimed it was due to Americans willingness to stay at home instead of work that brought about the results.

The ventilator shortages of which we were all gravely warned have not yet come to pass.

So, What’s the Big Deal with Ventilators?

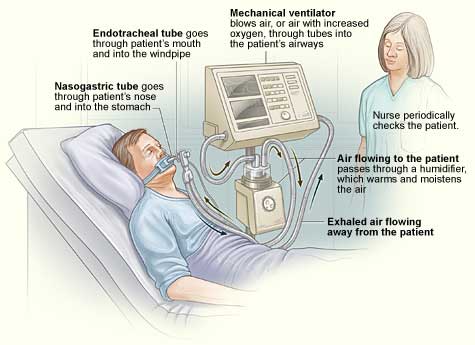

A ventilator is a machine that provides mechanical ventilation by moving breathable air into and out of the lungs, to deliver breaths to a patient who is physically unable to breathe, or breathing insufficiently. Some of us may remember what was called the iron lung, a form of noninvasive negative-pressure ventilator widely used during the polio epidemics of the twentieth century.

A ventilator is a machine that provides mechanical ventilation by moving breathable air into and out of the lungs, to deliver breaths to a patient who is physically unable to breathe, or breathing insufficiently. Some of us may remember what was called the iron lung, a form of noninvasive negative-pressure ventilator widely used during the polio epidemics of the twentieth century.

Numerous advances have taken place in ventilator design over the decades since then.

Some critical care physicians question the widespread use of the breathing machines for Covid-19 patients, saying that large numbers of patients could instead be treated with less intensive respiratory support. In March 2020 the USFDA suggested that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices may be used to support patients affected by Covid-19. This noninvasive method has been used for patients who require a ventilator only while sleeping and resting, mainly employing only a nasal mask.

The more invasive method used with a mechanical ventilator requires tracheal intubation, which for long-term ventilator dependence will normally be more comfortable and practical.

Mechanical ventilation is often a life-saving intervention and has been called “the device that becomes the decider between life and death” for COVID-19 patients. Since COVID-19 was a respiratory disease sending about 5% of detected cases to rely on the device, a shortage was deemed critical.

Ventilators shortage is endemic in the developing world, and in some cases doctors have used triage strategies that grade the patient on dimensions such as: prospects for short-term survival; prospects for long-term survival; stage of life-related considerations; pregnancy and fair chance. That prospect scared the American medical establishment who demanded their government prevent that from happening in America.

Far from being the magical cure for Covid-19, the more invasive method used with a mechanical ventilator also carries potential complications including pneumothorax, airway injury, alveolar damage, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and ventilator-associated tracheobronchitis. Other complications include diaphragm atrophy, decreased cardiac output, and oxygen toxicity. One of the primary complications that presents in patients mechanically ventilated is acute lung injury (ALI)/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ALI/ARDS are recognized as significant contributors to patient morbidity and mortality.

There is growing evidence pointing to how often the machines fail to help.

While there are tens of thousands who died from Covid-19, the numbers of patients dying in intensive care units and on mechanical ventilation is yet unknown. It was reported, 80% of NYC’s coronavirus patients who are put on ventilators ultimately die. We also have published information from the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Center (ICNARC) in the UK. Of 165 patients admitted to ICUs, 79 (48%) died. Of the 98 patients who received advanced respiratory support—defined as invasive ventilation, BPAP or CPAP via endotracheal tube, or tracheostomy, or extracorporeal respiratory support—66% died. In a U.S. study of patients in Seattle, only one of the seven patients older than 70 who were put on a ventilator survived; just 36% of those younger than 70 did.

“Contrary to the impression that if extremely ill patients with Covid-19 are treated with ventilators they will live and if they are not, they will die, the reality is far different,” said geriatric and palliative care physician Muriel Gillick of Harvard Medical School.